The Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Tropical Medicine (MITM) at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences has built a strong tradition of scientific inquiry through both basic and translational research, significantly advancing the available body of knowledge for some of the world's most devastating infectious diseases. In support of its mission and research vision, the department was recently awarded a major grant, a $15.6 million NIH infrastructure project to build and enhance the laboratories and expand its basic and translational research activities. Please see this GW Today article for more information on the building project and visit our photo gallery for photos of our new state-of-the-art research space.

- The Research Center for the Eradication of HIV

-

The declared goal of The Research Center for the Eradication of HIV is to develop novel and innovative HIV prevention and eradication therapies through basic science, and to rapidly translate these findings into the clinic. The Center is comprised of the laboratories of Douglas Nixon, MD, PhD, Michael Bukrinsky, MD, PhD, David Leitenberg, MD, PhD and Rebecca Lynch, PhD.

HIV/AIDS

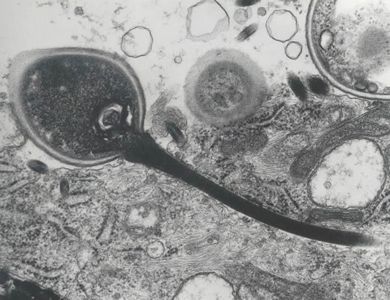

The infection with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 (HIV-1) and the resulting Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) is a global pandemic that affects, as of 2014, more than 37 million people worldwide with over 2 million new infections and over 1 million deaths each year. Although the bulk of the epidemic is in Sub-Saharan Africa, it affects almost every country in the world.

HIV has such devastating effects on the human immune system because it infects specific types of immune cells called CD4 T cells, which are essential for coordinating regular immune responses. Over time, the HIV-induced death of these crucial immune mediators causes AIDS, a state of progressive immune failure in which the body is susceptible to cancers and opportunistic infections. While antiretroviral drug treatments have dramatically improved the lives of those who can afford and tolerate these drugs, there is a 10-year life expectancy gap between people who are uninfected with HIV and those that are HIV-infected and under treatment. Thus, there is still an urgent need for better treatments and an effective vaccine.

The research in Dr. Nixon’s lab is focused on mechanisms that human host cells employ to control HIV replication as well as viral persistence and latent HIV reservoirs in chronically HIV-infected individuals. The lab is also exploring novel biological HIV eradication strategies and vaccine approaches.

The studies in Dr. Bukrinsky’s lab aim at elucidating the links between HIV infection, inflammation and cardiovascular diseases, which occur at an increased frequency in HIV-infected individuals. The lab furthermore investigates anti-viral factors produced by the human host cell to counteract viral proteins and develops new therapeutic agents to treat inflammatory diseases in HIV patients.

The research focus of David Leitenberg, MD, PhD, is the regulation of survival and cell fate decisions in T cells, which is critical for the rational design of therapeutic strategies to enhance protective immune responses to infectious diseases and tumors, as well asoradly neutralizing HIV antibodies and vaccine development. the understanding of harmful immune responses in autoimmune and inflammatory disorders.

The research in Dr. Lynch's lab is focused on the investigation of the properties of broadly neutralizing antibodies on both HIV and HIV-infected cells to explore new avenues for the development of potent preventative and therapeutic agents against HIV infection.

MITM also accommodates the George Washington Biorepository, a comprehensive, state-of-the-art resource of biospecimens and clinical data designed to facilitate HIV/AIDS and cancer research, under the direction of Sylvia Silver, D.A.

- The Research Center for Neglected Diseases of Poverty

-

Research at The Research Center for Neglected Diseases of Poverty focuses on the pathogenesis of parasitic diseases, including helminth infections and toxoplasmosis. Parasitic infections remain the number one disease burden for humans in developing countries. Current estimates suggest that over one billion people worldwide are infected with at least one parasite species. The impairment of health and normal development of infected populations results in decreased productivity, persistent poverty, and poor socioeconomic development in many tropical and subtropical countries.

The Research Center for Neglected Diseases of Poverty is comprised of the laboratories of Jeffrey Bethony, Ph.D., Paul Brindley, Ph.D., David Diemert, M.D., John Hawdon, Ph.D., Galadriel Hovel-Miner, Ph.D. and Imtiaz Khan, Ph.D.

Many of the parasitic diseases of humanity are caused by infection with helminths. These parasitic worms live in the blood vessels, digestive tract or other organs of their human host, where they receive nourishment while depriving their host of blood and nutrients. This leads to anemia, malnutrition, weakness and growth retardation in particular in children, and frequently constitutes a crippling burden on inhabitants of impoverished regions of the developing world. In addition, infection with some parasitic worms, including the liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini and the blood fluke Schistosoma haematobium, cause infection-related cancers. Historically, helminths have been difficult to study because of the absence of suitable laboratory rodent models and their complex developmental cycles.

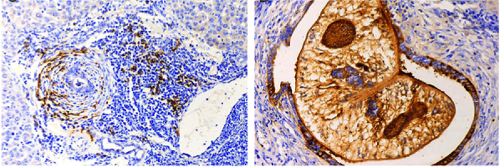

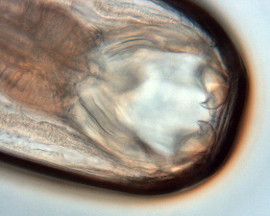

Schistosoma (blood flukes), Opisthorchis viverrini (liver fluke) and helminth infection-associated cancers

Blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma are parasitic flatworms that infect humans by penetrating the skin after contact with water contaminated by the parasite. Aquatic snails are the main route of disease transmission. Adult worms reside in the blood vessels of the liver, intestines and pelvic organs and feed on red blood cells. Schistosomiasis is widespread throughout sub-Saharan Africa, in northern South America, and East Asia. With 210 million people infected globally, schistosomiasis or bilharzia is the most important helminth disease of humanity in terms of morbidity and mortality and is considered to be the second most socioeconomically devastating parasitic disease (after malaria) by the World Health Organization (WHO). Chronic infection with Schistosoma haematobium can cause bladder cancer.

The liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini, is a parasitic worm endemic in Southeast Asia, in particular in Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand. Related liver fluke infections occur in China, Russia and Western Europe. Infection with the liver fluke is acquired by eating undercooked or raw infected fish. The adult worms inhabit the bile ducts of the liver, where they can live and produce eggs for many years or even decades. Chronic opisthorchiasis leads to lethal bile duct cancer in many of the infected individuals, most of whom reside in impoverished, rural communities.

In collaboration, Dr. Brindley’s and Dr. Bethony’s labs focus on the pathogenesis of liver fluke infection and infection-related bile duct cancer, including metabolites the parasite secretes into the host and the chemical changes and composition of the microbiome of the biliary tree and gastrointestinal tract. The researchers also aim to identify biomarkers for parasite-associated cancers. In addition, the role that individual parasite genes play for the infectivity of these carcinogenic worms is assessed as a means of identifying new avenues of anti-parasite interventions. Lab-based as well as cohort-based studies are carried out in Opisthorchis viverrini endemic regions in Northeastern Thailand in collaboration with colleagues at Khon Kaen University, Thailand, and others, and in Schistosoma haematobium endemic regions in Angola together with colleagues from the University of Porto, Portugal.

Hookworm

Three species of hookworm, Ancylostoma duodenale, Ancylostoma ceylanicum and Necator americanus, can infect humans. Hookworm infection, which is acquired by contact with contaminated soil, affects more than 700 million people worldwide. The larvae penetrate the human skin and eventually settle in the small intestine. Here the worms attach to the intestinal wall and feed on blood, which can cause severe anemia, malnutrition and growth, and cognitive retardation, particularly in children.

At MITM, the research of Jeffrey Bethony, PhD, David Diemert, MD and John Hawdon, PhD is focused on developing an effective hookworm vaccine and characterizing hookworm biology.

Dr. Hawdon’s lab is interested in developing genetic tools to investigate the molecular basis of hookworm pathogenicity and host immune function, as well as implementing alternative control strategies, such as improvements in sanitation in hookworm endemic areas.

With Dr. Bethony’s and Dr. Diemert’s labs, MITM hosts the clinical immunology laboratory and clinical trials unit of the Sabin Vaccine Institute Product Development Partnership (Sabin PDP), an Albert B. Sabin Vaccine Institute-funded partnership to develop new vaccines for neglected tropical diseases. In collaboration, both labs are currently running five phase 1 clinical trials for a hookworm vaccine: Two of these trials are carried out at the Children’s National Hospital and the GW Medical Faculty Associates in Washington D.C., two in collaboration with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) in Belo Horizonte and Americaninhas (Minas Gerais) in Brazil and one in Lambaréné in Gabon. In addition, both labs are also involved in the Schistosoma mansoni vaccine project.

Toxoplasma gondii and Microsporidia

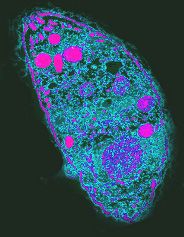

Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular protozoan parasite that can be found worldwide. It is one of the most common parasites infecting humans and there are estimates that up to one-third of the global population could be chronically infected with toxoplasma. Cats are the definitive host for this parasite, although it can asexually reproduce in any warm-blooded animal. The infection of humans can occur via multiple different routes, ranging from blood transfusions to eating contaminated undercooked meat or vegetables. Toxoplasma can also be transmitted from mother to child through the placenta during pregnancy and can cause abortion of the fetus. Toxoplasma gondii causes the disease toxoplasmosis, one of the most frequent opportunistic diseases in HIV patients, and has been shown to alter the behavior of infected rodents in ways to make them more likely to be consumed by cats. Recently, the disease threat has become more acute by the appearance of several new aggressive strains of Toxoplasma gondii in Brazil.

Microsporidia are a large group of over 1000 highly divergent species of unicellular fungi, formerly categorized as protozoans. They are parasites of a wide range of vertebrate and invertebrate hosts, including at least 15 species recognized as human pathogens. The resulting disease microsporidiosis is an intestinal infection that causes diarrhea and can lead to severe wasting in immune-compromised individuals such as AIDS patients, as well as be problematic in certain groups of non-HIV infected persons including the elderly, travellers, children, organ transplant recipients, cancer patients and diabetics.

The laboratory of Imtiaz Khan, PhD is interested in characterizing the human immune response to Toxoplasma gondii infection, in particular, the memory T cell response and the quality and duration of the T cell response during recurring infection, as well as the protective immunity in response to infection with Encephalitozoon cuniculi, a microsporidia species relevant for human disease.

African trypanosomes

Trypanosomes are unicellular protozoan parasites infecting a wide range of mammalian hosts, including humans and domestic animals. Most of these parasites are transmitted by insects, and some species cause a chronic and often fatal diseases in both humans and animals. In Africa, trypanosomes inflict a heavy socioeconomic burden due to their detrimental effect on human welfare and agricultural development. The species Trypanosoma brucei is transmitted by tsetse flies and is responsible for epidemics of the fatal human disease sleeping sickness in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sleeping sickness occurs in 36 African countries and causes the second-highest mortality rate after HIV/AIDS in some parts of the continent. However, the largest economical impact is probably made by trypanosome species affecting cattle by reducing milk and meat production.

By changing the expression of proteins on their cell surface, trypanosomes efficiently evade the host immune system. The laboratory of Galadriel Hovel-Miner, PhD, focuses on the molecular biology of this antigenic variation in African trypanosomes to uncover new factors and mechanisms towards the development of future drug targets for the treatment of neglected tropical diseases.